Hope

Long ago, when the Earth was young, I enrolled in a poetry workshop led by Liz Ahl, and one of the assignments was to write a “how-to poem” — that is, a poem instructing readers on how to do something. I wrote a poem called “How to Have Qualms”, and though I have no desire to return to the poem itself, I am fond of the title, because if there is one thing I know how to do, it is how to have qualms.

Today, my qualms are about the idea of hope, particularly as it relates to education. Things are bad in the institutions of higher education in the US, especially among the supposedly public schools, schools which for many years now have seen their funding cut, their missions perverted, their students burdened with debt, their staffing slashed, their faculty adjunctified. In such an environment, it’s understandable that people would ask where to find hope.

I wonder, though, if hope is the wrong thing to look for. Certainly, even if hope is necessary, it’s likely in short supply right now. So what else might we seek?

I’ve rarely in my life ever succumbed to a feeling I would call hope. Yes, fleeting, here and there, a bit of hope, sure. Like happiness, which is also fleeting and short-lived, a pleasant enough thing as it flashes by, but it only lives in flashes. (Contentment, rather than happiness, is my goal.) This could as much be a matter of personality as anything else. My view of life and the world has been, for as long as I remember, founded on pessimism.

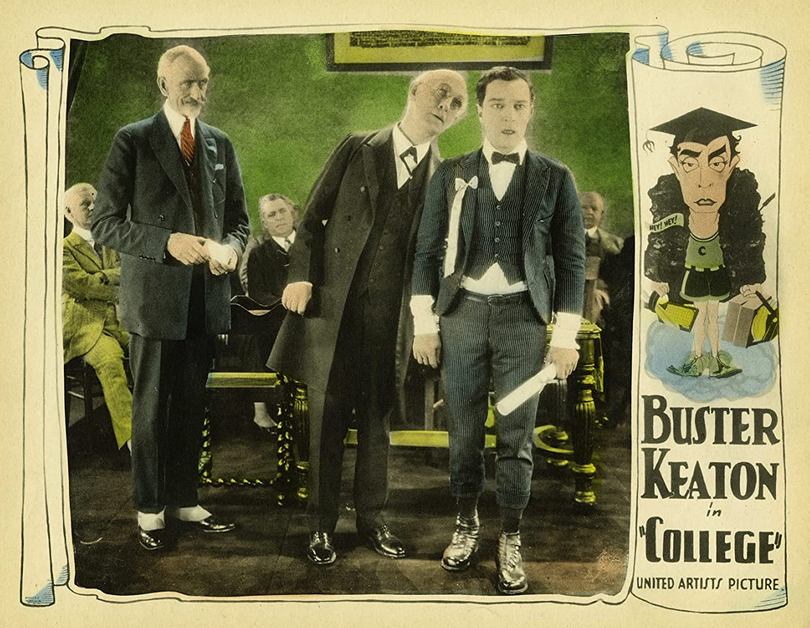

Even in elementary school I was drawn to horror stories, because horror stories fit with my understanding of life as a condition of anxiety, terror, and suffering. In high school, I discovered Existentialism and, even more importantly, Theatre of the Absurd — and I finally felt that I was among my people. While I was philosophically interested in Camus, I was temperamentally drawn much more to Beckett, because the meaningless and suffering of existence deserves laughter. (A dark, even morbid, laughter, but laughter nonetheless.) Beckett’s devotion to Laurel & Hardy and, especially, Buster Keaton linked with my own young adulation of the Marx Brothers, particularly their most absurdist films (Duck Soup being the apotheosis of this, though Horsefeathers is most applicable to academia). I have never thought the emptiness of existence and the meaninglessness of the universe require tears more than they welcome laughter.

Laughter at absurdity is one thing; hope quite another. When it comes to hope, I’m more on the side of the dour Dr. Schopenhauer:

As a reliable compass for orientating yourself in life nothing is more useful than to accustom yourself to regarding this world as a place of atonement, a sort of penal colony. When you have done this, you will order your expectations of life according to the nature of things and no longer regard the calamities, sufferings, torments, and miseries of life as something irregular and not to be expected, but will instead find them entirely in order, well knowing that each of us is here being punished for existence and each in our own particular way.

Though the above is hardly something you should express if you want to be the life of a party, nonetheless it does not need to be the cause of depression and cruelty, as Schopenhauer notes:

The conviction that the world, and therefore humans too, is something which really ought not to exist is in fact calculated to instil in us indulgence toward one another: for what can be expected of beings placed in such a situation as we are? From this point of view one might indeed consider that the appropriate form of address between person and person ought to be, not monsieur, sir, but fellow sufferer, compagnon de misères. However strange this may sound it corresponds to the nature of the case, makes us see other people in a true light and reminds us of what are the most necessary of all things: tolerance, patience, forbearance, and charity, which each of us needs and which each of us therefore owes.

Schopenhauer, Essays and Aphorisms (Penguin), trans. Hollingdale (translation adjusted)

Or, as another great philosopher, Tom Waits, once sang: “Misery’s the river of the world — everybody row!”

Hope? Nope!

A friend of mine is a writer whose work often touches on themes of the environment, and in the last couple years interviewers have commonly asked him if he has hope, how he has hope, what gives him hope, etc. A reasonable question, given the likelihood that the future is going to be even more awful than the present. He has taken to redirecting the question, however. Hope, he says, is not really relevant. Have hope, don’t have hope, the situation is what it is. That doesn’t mean we should abandon activism, toss our hands in the air, and give up on mitigating the disasters all around us. That would be stupid. Reducing suffering is a good thing, because even though suffering prevails (that is the condition of life), suffering can be lessened. Less suffering, even in the midst of lots of suffering, is still less suffering. While it’s still possible to avoid a 2°C rise in global temperatures, in many practical ways it seems unlikely, which is unfortunate … but even so, we could still try to avoid a 3° rise or a 4° rise or a 5° rise, because 3 is significantly better than 4, and 4 is better than 5. (Though get much beyond 5 and human life is rather hard to sustain at all.) This isn’t about hope, it’s about minimizing suffering as much as possible under the circumstances.

We’ve all had an immediate experience of this situation during the pandemic. The US, for instance, might not have been able to prevent the first 50-100,000 deaths in our country. But we sure as hell could have prevented 500,000 deaths. That we didn’t does not mean we should give up trying to prevent more deaths. As I write this, we’re approaching 600,000 dead in this country. We can avoid hitting 1 million this year, and we should. That has nothing to do with hope and everything to do with trying to limit or reduce suffering.

Similarly, higher education is a slashed-and-burned field of chaos. As an institution, particularly a public institution, if it hasn’t become a world of hurt already, it will soon. My own school is suffering program eliminations, workload adjustments, and massive staffing shortages and instability after the Board of Trustees offered a lucrative deal to anyone willing to retire early or just leave. Quite rationally, a lot of people took them up on the offer, so by my rough calculations we’re losing 20-30% of tenured faculty and who knows how many non-tenure-track faculty and staff. Most are not being replaced. And this isn’t because the university was bloated with workers before. The work isn’t going away, it’s just being piled onto a smaller and smaller workforce. We had already suffered significant losses of employees, particularly staff, over the last decade. In office after office, jobs that previously were done by three or four people are now done by one, if they are done at all. You don’t need to be a visionary to be able to imagine what this has done to morale. Meanwhile, the entire state government is controlled by the party that hates the idea of the public good and doesn’t much like the idea of public education. Most of the other viable sources of funding beyond the state are some branch of Disaster Capitalism, Inc. Happy days!

Abolish the University?

Do you want more pessimism? Or not exactly pessimism, but a sort of nihilism about the possibility of higher education ever being worthwhile while trapped in capitalism. Friends, I give you FT, who argues that if you pretend toward an anti-capitalist ethic, it makes most sense to abolish the university as an institution:

It is not possible to abolish capitalism without abolishing the university as we know it. The university as we know it cannot survive the end of capitalism and therefore the continued existence of the university is antithetical to the horizon of any anti-capitalist imaginary…

To admit that the university can’t exist without capitalism is to admit that without capitalism you wouldn’t have this job or this career or this office and really…who would you be? This is a form of what Gramsci calls “institutional fetishism.” It’s a common component of hegemonic ideology: the worker learns to think of the workplace as an institution separate from their labor, and comes to believe that they are permitted to labor by the grace of the institution, when in fact the institution only exists by virtue of the worker’s labor. The tenure system works as an academic lottery: a lot of smart people do a lot of work for free or dirt cheap in the hopes of one day striking it rich. It’s a rot, but hegemony is a hell of a drug.

Some parts of this argument seem to me right on target (especially for wealthy research universities), but I have qualms. The writer allows their bitterness at academia and academics to muddy insights. Institutional fetishism is very real in academia, and definitely leads to tremendous amounts of disempowerment as workers align themselves with an idea of the institution rather than an idea of the workers’ labor, or even of basic self-respect. But we can dispense with institutional fetishism, and maybe even capitalism, and still have teachers and students, as well as a lot of the ideals of the university, an institution that pre-dates capitalism and even in these hypercapitalist times has held onto some of the elements of a feudal guild structure (for better or, often, worse).

Who I would be without capitalism is a more content person. Probably still a teacher, because it’s what I know how to do. Heck, I don’t even need all of capitalism to go away; I’d be thrilled just to have a good social safetynet and universal health insurance so I didn’t feel so tied to having to work at this one job and could instead experiment more with life. (So maybe FT is right and I wouldn’t still be a teacher without capitalism. But it’s easier for me to imagine the end of capitalism than it is to imagine myself not teaching. I just wish I didn’t feel so obligated to this specific job because I don’t have another good way to get health insurance. Employers, of course, benefit from our sense of there being few alternatives, because that allows them to shape the workplace into what they want it to be, since there is less chance that we will leave if we don’t like what they do.)

If I had hope, it would be hope for the end of capitalism and the end of institutions as we know them. I would love to abolish the university as it currently exists, even though I’ve got the highly-coveted job of being a tenure-track professor. I would love to abolish tenure itself — it’s a necessary evil at the moment to preserve some bits of power against the predations of management, but it’s inequitable (by design), it fuels hierarchy, and it is too often used to set workers against each other rather than to unite them. I would happily give up tenure if it would turn the university into a workers’ cooperative. Right now, though, giving up tenure would mean giving administrations and legislatures more power, even at institutions with good unions. (If there is anything like hope for the short term, it resides in unions, especially if tenured faculty participate thoughtfully and generously in those unions.)

But we live in capitalism and I have bills to pay and the only thing I’m marginally employable for is teaching, so here I am. Hello, compagnons de misères!

Power/Empowerment

Though I do not have hope, I do not have despair, either. (Or, at least, I don’t have more despair than usual. Life is SNAFU: Situational Normal, All F’ed Up. Keep pushing your rock, Sisyphus.)

The analytical concept I always find myself returning to is power. (A friend once called me an inveterate Foucauldian, but before I’d read anybody of such theoretical complexity, I had fallen under the spell of the anarchism of Peter Kropotkin, Emma Goldman, Paul Goodman, and Ursula Le Guin.) Indeed, I think rather than popular ideas of hope, empathy, etc. we might be better off framing things through questions of power and, as I said above, suffering.

For instance, consider empowerment. What would it actually mean to seek empowerment, and what would it mean to empower?

If I say that my goal is to empower students (a good and reasonable goal) then what practices will lead to that? How will I know that students are empowered? Considering that much teaching is based on the disempowerment of students, how might I reconfigure my teaching to empower, and what might that mean for my role? How does my desire to empower my students connect to the interaction of the institution and the students — and how should that inform my teaching?

Stuart Hall said of Antonio Gramsci’s understanding of power: “every form of power not only excludes but produces something”. In our quest to empower, what do we seek to exclude and to produce? What does the power within our own teacherly role exclude and produce? What does institutional power exclude and produce?

Further, how does our relationship to power produce or relieve suffering?

Compassion and Generosity

One reason why I resist the idea of hope is that the way it gets used in these sorts of contexts feels a bit too teleological for my tastes, even utopian. Things, I tend to believe, don’t get better; rather, suffering shifts its location. This is perhaps why I find Taoism and Buddhism far more interesting as religions than Christianity. This doesn’t mean I just want to mope around, though. I am inspired by a chapter in Pankaj Mishra’s An End to Suffering: The Buddha in the World titled “A Spiritual Politics” — and I say that as someone who immediately resists the word spiritual about anything — in which Mishra argues that a kind of decentralized idea of politics developed in the early Buddhist teachings:

(Buddha’s) model for the internal structure of the sangha [Buddhist community] was the small republic in which communal deliberation and face-to-face negotiation were possible. … He saw consensus as of the utmost importance to the life of the sangha. … Controversy, whenever it arose, could be settled by the method of the dissenting individuals removing themselves and forming a new group. … The Buddha’s early effort to accommodate dissent, and acknowledge the plurality of human discourse and practice, later saved Buddhism from the sectarian wars that characterize the history of Christianity and Islam; and the Buddha’s emphasis on practice rather than theory kept his teachings relatively free of the taint of dogma and fundamentalism.

pp. 284-285

This was also an idea of politics (and religion) that emphasized the necessity of practicing generosity and compassion — and built in opportunities for that practice. Monks would go out each day to beg, opening an opportunity for laypeople to practice generosity and compassion. The presence of beggars gave passersby a concrete way to enter into a generous and charitable frame of mind while also, via their charity, taking care of the immediate needs of the monks — a win-win, really, because the donor gets to strengthen the habit of charity while the monk gets to eat. By begging, the monk performs a service to the larger community while also providing for the self.

Mishra writes:

For the Buddha as much as for Plato, life in society was the inescapable obligation faced by human beings. There was no private salvation waiting for them. In fact, as the Buddha defined it, liberation for a human being consists of entering a non-egotistical state, where he felt the conditional and the interdependent nature of all beings.

p. 288

This did not, however, lead early Buddhists to advocate for a state that foisted its obligations off on charity. Instead, according to Mishra, early Buddhist teachings about government and society proposed a strong welfare state. Rulers were advised to allow immigration and to encourage neighborliness, establish hostels, support doctors, care for the sick and injured, lower taxes, save profits for times of trouble and scarcity, subsidize farmers, provide capital for investment to merchants, and pay government workers fairly. A ruler’s authority came not from heredity, social position, or strength, but from rightness of action. Rulers who did not act on compassion, generosity, and an understanding of interdependence did not have legitimate authority.

I am not a scholar of Buddhism, and so I do not know if Mishra’s interpretation of its early history is correct, but I also don’t care. The vision Mishra presents is a valuable one for thinking about how compassion may be a structurally useful force for shaping power and dealing with the inevitability of suffering. It is also useful for thinking about authority.

Authority and Empowerment

Our schools are institutions of hierarchy, and hierarchy maintains itself through force and exclusion, through power, through cruelty. Hierarchical institutions give some people power and authority, other people less, and thus the hierarchy preserves what those with authority most want to preserve — which, more often than not, is first and foremost their own power. Power corrupts because it is seductive and addictive.

To avoid the seductions, addictions, and corruptions of power, power must flow freely and generously, not be held onto or hoarded. We should analyze power so that we can figure out how power can be dispersed and diffused.

The question I have for anyone in authority is: How much of your power can you give away? What limits the amount of power you can give away?

Giving power away is empowerment. Hoarding power is egotism. Here I turn to my favorite of Le Guin’s anarchist texts, her adaptation of the Tao Te Ching. Here, the first few lines of chapter 38, which she titles “Talking About Power”:

Great power, not clinging to power,

has true power.

Lesser power, clinging to power,

lacks true power.

Early in my teaching career, I clung to power. This was because I was young, inexperienced, insecure. Good mentors helped me see that the best teachers work hard to make themselves unnecessary. This is also terrifying. It continues to be terrifying — just this term, after a couple decades teaching, I was overcome with a feeling that I wasn’t doing enough in my classes. (Despite all the evidence that my students were learning just fine without my constant nagging and intervening.) This feeling flourished, almost to paranoid levels in me, because we are living in difficult times, both in the world and in my particular institution, and insecurity makes us (or, at least, me!) cling to power. But as any good Buddhist will tell you, you must cling to nothing. (And only to nothing!)

Empowerment requires an analysis of power so that that power may be subjected to generosity. This is necessary as a model, too. We should not empower others only so that they may themselves egotistically cling to that power. Instead, we must empower people so that they are able then to empower others. This is how we bear the suffering that is existence. So much of that suffering is the result of people clinging to power.

Destroy the Ring

Perhaps an analogy is appropriate here. (A literary one, but also kind of nerdy. If you’re not feeling nerdy, you might want to skip this section!)

I appreciate Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings because it seems to me a beautiful, terrifying, and deeply true allegory of power. Power is attractive, addictive, and destructive. It should not be centralized. There should not be one ring of power — it is too much even for wizards to resist. Only the most humble can bear it for long without becoming monstrous, and even they will be hollowed out by it. The one ring must be destroyed, its power dispersed.

What we must ask of authority is not, “Are you Sauron?” Most authority is not pure evil. Rather, we must ask: “Are you Isildur, who, having cut the ring of power from the finger of Sauron, preserves it? Or, perhaps you are Boromir, who thinks the power of the ring can be harnessed for your own idea of good?”

The one ring must always be destroyed. The quest to do so will leave many scars, but its necessity is clear and absolute.

New Conjunctures

If there is hope, that hope lies in the dispersal of power, the generous giving away of power — empowerment. I do not think of it as hope, though; I think of it as the necessary task.

I am writing this post in quiet response to a recent presentation by Joshua Eyler, “On Grief & Loss: Building a Post-Pandemic Future for Higher Ed without Losing Sight of Our Students and Ourselves”. This was a profound presentation that zeroed in on essential problems and questions in a way that feels both affirming and inspiring. It is also a call to analyze, wield, and disperse power.

Though the ruling ring of power must be destroyed, it may sometimes be necessary to use it to keep it on the path leading to the fires of Orodruin, where it will be destroyed. Now is the time when we as educators must band together in fellowship, and do whatever it takes to keep what we value from being destroyed. If that means wielding — even consolidating — power, so be it. Sometimes, an analysis of power shows that power cannot be dispersed until it is seized. We cannot empower students if we are ourselves disempowered.

We cannot return to whatever “normal” was before the pandemic, either in life generally or in our specific work. We must, as Josh Eyler says, refuse to let the conversation turn back to norms that were, in fact, bad to begin with. We must insist that the traumas of the last year and a half be acknowledged and worked through, that grief be recognized, and, on a more positive note, that new flexibilities and creativities be continued — and even strengthened.

This is not, though, Year One of a revolution. We are in the flow of existence, and while this may, in fact, be a meaningful and revolutionary moment of crisis, it is also the product of long history. That must be acknowledged. Some of the failures and miseries of this experience were unavoidable consequences of a global health crisis or unavoidable consequences of living in capitalism; but some of them were products of the attitudes and assumptions that structure our institutions.

And so I will end by quoting Stuart Hall, the final words of one of his last statements, a beautiful essay now published as “Through the Prism of an Intellectual Life” in volume 2 of Hall’s Essential Essays (JSTOR link):

I commend to you the duty to defend [the academy] and the other sites of critical thought. I commend you to defend it as a space of critical intellectual work, and that will always mean subverting the settled forms of knowledge, interrogating the disciplines in which you are trained, interrogating and questioning the paradigms in which you have to go on thinking. That is what I mean by borrowing Jacques Derrida’s phrase “thinking under erasure.” No new language or theory is going to drop from the skies. There is no prophet who is going to deliver the sacred books so that you can stop entirely thinking in the old way and start from year one. Remember that revolutionary dream? “Year One”? “From now on, socialist man”? This is when the new history begins! Today, the dawn of the realm of freedom! I am afraid the realm of freedom will look mostly like the old realm of servitude, with just a little opening here and there toward the horizon of freedom, justice, and equality. It will not be all that different from the past; nevertheless, something will have happened. Something will have moved. You will be in a new moment, a new conjuncture, and there will be new relations of forces there to work with. There will be a new conjuncture to understand. There will be work for critical intellectuals to do. I commend that vocation to you, if you can manage to find it. I do not claim to have honored that vocation fully in my life, but I say to you: that is kind of what I have been trying to do all this while.

Thank you. I am beyond grateful for this piece and will return to it again and again.