Since the title of my recent book is The Last Vanishing Man (and the title story includes historically-accurate descriptions of stage illusions), it shouldn’t be a surprise that I love everything having to do with magic — the lore, the history, the illusions, the beliefs in some sort of “real” magic (what does “real” mean?), all of it. I’ve never been a very good performer of magic, though I’ve practiced various effects since I was a junior in college when, for ridiculous reasons having to do with keeping a major donor to the school happy, my roommates and I were asked to found a magic club at our university, even though none of us knew the first thing about magic. (We were environmental activists. I think the school saw it as a way not only to appease the major donor but also to keep us from embarrassing the school on CNN, as we had recently done. But that’s another story!) With the university’s resources at our disposal, we we able to learn from quite a few significant magicians in New York. It was fun, wild, and weird.

I lack both the guile and the manual dexterity to perform magic well, but I’ve studied many books on magic in all its forms, and I’m fascinated by recent research on magic, psychology, and neuroscience — see, for instance, the work of Gustav Kuhn. If I could have been anybody in history for a week or two, I would like to have been Ricky Jay, who knew all sorts of things I would love to know. I’m quietly obsessed with what magic can tell us about storytelling (see the recent interview Jeff VanderMeer did with me at LitHub for some brief thoughts on misdirection and narrative). In fact, since I see a sabbatical somewhere in my future, I’m toying with the idea of writing a whole book about storytelling and magic.

But all of this is getting ahead of myself and more than this little blog post can bear.

Earlier this week, in a conversation with colleagues after The Amazing Martha (Burtis) gave a 15-minute presentation on transparency in teaching, we got to talking about the teacher’s bag of tricks. The Great Robin (DeRosa) said that as a young teacher she relied on some tricks to get students engaged, to bring them toward particular revelations, etc., but as she delved deeper into the philosophy and science of learning, she began to feel that this was unfair, that tricks are a kind of power move, that they may be useful for conveying certain bits of content but they aren’t really good for deep learning. Except maybe they are, sometimes, in some ways? She wasn’t sure, and we came to no conclusions about this. Robin brought up a point I had made in a keynote presentation that she, I, and one of our librarian colleagues gave at the beginning of the summer to a bunch of academic librarians in New Hampshire.

What I talked about then was the value of making visible the invisible labor we often take for granted. Working in a library building, but not a librarian myself, I discovered that librarians do all sorts of things even I, a lifelong power-user of libraries, was unaware of. In fact, the librarians worked hard to keep a lot of their labor invisible, since it didn’t seem relevant to what patrons needed. The problem was, it then made it easy to undervalue the librarians’ labor. On the one hand, this increases exploitation. But on the other hand, I found a lot of what the librarians did quite interesting. It increased my appreciation for their skills and knowledge.

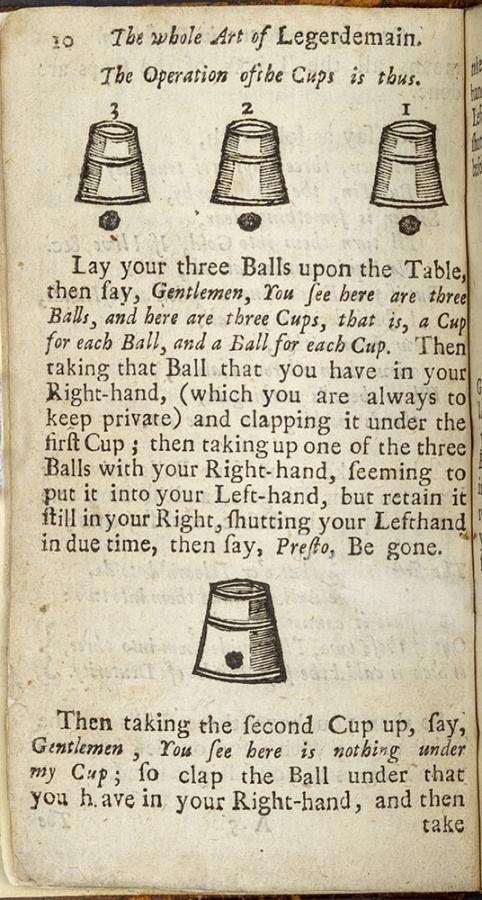

As an analogy, I shared the story of what Penn & Teller do with one of the oldest magic tricks in the world, the cups and balls. For decades now, they have performed the cups and balls first in a traditional manner, the only innovation being that they use red plastic cups and tinfoil balls. It’s amusing, because the trick performed by skilled magicians is always amusing, but it’s not much more than that — it’s still just, you know, the cups and balls.

So then they do it again, this time with clear plastic cups, revealing the entire technique. (Generally, revealing techniques is a crime that will get you shunned and ruined in the magic community, but revealing the cups and balls at this point is like telling people [spoiler alert!] that Oedipus killed his father and married his mother.) Here’s a good example of the Penn & Teller routine on the Jay Leno show. (For an even more elaborate trick and reveal, see their performance of “Lift Off”.)

Penn & Teller made the cups and balls interesting for an audience again — and they did so by stopping it from being a trick. What they realized is that the technique performed with extraordinary skill is in fact more captivating than the illusion the trick provides. You could learn the cups and balls in 15 minutes. Children do! But it would take you countless hours, days, and years to become as good at performing it as Penn & Teller.

My message to librarians was that in a world where libraries have been turned into culture war battlegrounds, and where universities are looking for any place they can cut staff, it’s politically vital to reveal the invisible labor of librarianship. But also: a lot of the skilled work librarians do is more interesting than they may think, and they shouldn’t hide it all away. Librarians are wizards!

As Martha talked about transparent teaching, and we continued the conversation about magic and tricks and what is fair or unfair, I couldn’t help but think about why the study and philosophy of magic so entrances me, and has for 25 years.

Magic is about invoking a sense of wonder. But it’s also about other things — attention, memory, perception, the instability of reality. Some magicians like the sense of power over an unwitting audience, enjoy putting one over on people, love the tricksiness of the trick. Plenty of magicians have taken their techniques from con artists, after all. But many magicians actually bristle at the word trick. (Effect is often preferred.) Simply fooling an audience gets old fast. We’re all easy to fool, not because we are fools, but because our brains and senses work in particular, sometimes predictable, ways. Without even necessarily knowing what they were doing, magicians have exploited these features of our neurobiology for centuries. Magicians, con artists, psychologists, and teachers all make their living from studying some of those predictable ways that humans perceive, think, and remember.

In a valuable little book for magicians, Magic by the Numbers, Joshua Jay reveals the results of some academic studies of both magic and people’s feelings about it. A study Jay collaborated on polled people about what they like and dislike in magic performances. There were some interesting overlaps between their likes and dislikes. Audiences said that they like surprise, amazement, and trying to figure out the trick (novelty); they said they dislike repetition and cliché (lack of novelty). (There were unconnected likes and dislikes, too. For instance, probably nobody is surprised that most people don’t like traditional, “cheesy” magicians dressed in a tux. For some reason, a lot of performers are attached to the most awful schmaltz, but audiences at most tolerate it.)

Various studies of the brain and memory have shown that surprise is actually a key to memorability and to learning. Under the right conditions, novelty is highly pleasurable to most people, and more importantly it is memorable. We remember what is different, strange, new — what inspires curiosity. Gustav Kuhn points out in various presentations, articles, and his book Experiencing the Impossible: The Science of Magic that human infants are drawn to things they don’t understand. We are a curious species.

One of the important points that both neuroscience and the science of learning and teaching have shown is that curiosity diminishes when fear or anxiety grows beyond a certain point, so what we’re talking about is curiosity and novelty within an environment with a relatively low amount of anxiety and fear. (Not a zero amount. This is important! Motivation generally requires a certain modicum of anxiety. I am anxious to get this blog post written in the next hour or, at most, two because I need to get ready to meet up with friends later. That is a useful, productive anxiety. It is very different from somebody saying, “Write this blog post or you will lose your job.” That would be motivating, for sure, but the anxiety would overwhelm my ability to think and write well.)

A good magic show provides a safe environment for uncertainty. Magic creates cognitive dissonance: we see something we know to be impossible, and yet we have seen it. Our brains struggle to reconcile such impossible reality. The cognitive dissonance is pleasurable instead of terrifying because we know that we are in a safe environment. We are open to both wonder and exploration because we do not interpret the impossible reality as an immediate threat. It is unsettling, but it is contained within a larger context of comfort. Kuhn sometimes connects this to horror movies: part of the pleasure of a horror story is that you know you’re in a relatively safe spot in which to have these otherwise unpleasant feelings aroused.

Magic is easier to like than horror, I think, because magic is about curiosity and wonder rather than more negative emotions. (I write horror stories, so I say this with nothing against horror.) Magic and horror both rely on — and play with — belief. Magic explores and challenges what we believe to be possible and sets that against what we perceive to be happening in reality. Horror, which often overlaps with magic, has a somewhat more specific relationship to belief, a relationship I’ve written about elsewhere.

What does all this mean for teaching?

First, teaching too requires an understanding of belief. It is where epistemology and metaphysics converge. But belief is also psychologically important for the learner. We learn better when we believe ourselves capable of learning.

Another key lesson from magic for teaching is the importance of curiosity. Intellectual curiosity is a term I cherish — perhaps for purely selfish reasons, because it is the only thing that explains the weird pathways of my life. (I am easily interested in lots of things.) I think the teacher’s sacred duty is not to convey information but to inspire curiosity. Magic reminds us that that can be pleasurable. Remember: the features people say they like about magic performances are surprise, amazement, and, for about a fifth of a general audience, the joy of trying to figure out how it was done. (The general audience part is important. I remember a magician saying somewhere that this desire to figure things out increased to basically 100% when they performed for engineers at Google.) Surprise, amazement, and joyful curiosity are feelings we can provide for our students that will not only increase their pleasure in learning but actually increase their learning.

Let your teaching be surprising. Find ways to bring amazement to your content and materials. (Remember what brought amazement to you when you were learning what you are now teaching.) Create situations where students have something to work on figuring out.

Another useful insight for teachers from Joshua Jay’s studies concerns card tricks, and it’s a bit paradoxical. First, Jay (a highly skilled card magician himself) discover that audiences find card tricks to be some of the least memorable. Do a card trick for an audience and then ask them to summarize the trick and they will often struggle, particularly if the trick has a complex plot, as many card tricks tend to. Card tricks ask viewers to remember numbers and images, and by adding a long sequence of moves to that, they reduce how much an audience is able to remember of something they only see once.

Before we get to the somewhat paradoxical part, here’s another insight Jay shares (this one from some of Kuhn’s studies as well as others): the most effective techniques to force the spectator to choose a specific card without realizing they are doing so are the ones that are slowest, simplest, and seemingly fairest. Magicians love complicated forces requiring immense dexterity. Of course they do — that’s what demonstrates skill and art! Do a complicated force for a fellow magician and they will tip their tophat in respect. I’m not going to reveal what the most effective card force is, but I will say that if you polled magicians unfamiliar with the studies Jay cites, they would almost certainly rank the actually most effective one to be least likely to succeed. Plenty of magicians would never even dare perform it because it’s so simple that it seems the audience would almost certainly see through it immediately. That is not, however, what testing shows. Despite the force being so simple as to be able to be performed by a 5-year-old, and so blatantly obvious that you would expect even a 5-year-old would notice it, it consistently fools audiences.

These two things go together: audiences struggle to remember complex card tricks and they are tricked by, and consider fairest, a force that is so simple most magicians wouldn’t even dare use it.

The lesson? Complexity is tough on our brains. Keep it simple! Just like magicians, we teachers can learn from Thoreau: “Our life is frittered away by detail … Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity!”

However — here’s the paradox: The memorability of a card trick plot does not necessarily affect the pleasure an audience takes (or doesn’t) in a card trick. Context matters.

Let’s illustrate this and finish up by returning to Penn & Teller. Their popular TV show Penn & Teller: Fool Us has introduced all sorts of great magicians from around the world to viewers at home. There have been some legendary performances on the show. (Shin Lim’s legendary performances, particularly his first, demonstrate exactly what I’m saying here, for instance. That video doesn’t have 75 million views because it’s the most astonishing magic ever created. Lim was at the beginning of a now pretty spectacular career, and he was still developing as a magician. That video has 75 million views because it is presented in such a beautiful way — as Penn says at the end, lots of people use smoke effects, and they’re usually annoying. I expect Penn & Teller were less fooled than they said; they may not have known the exact techniques, of which there are at least a few for those effects, but they knew what was going on. What they were was astonished and moved.) But the moment that I love with all my heart is that of Dani DaOrtiz.

Spanish magic often has a chaotic element to it, perhaps largely due to the influence of Juan Tamariz, often said to be the greatest sleight-of-hand magician alive. Tamariz is, by all accounts, generous with his knowledge. Dani DaOrtiz was his student.

Even a great magician wouldn’t likely catch everything DaOrtiz does in his Fool Us routine without reviewing it a few times. Because he does so much! This was part of his strategy. He knew he had a certain amount of time and instead of focusing that time on a single elegant trick, he chose a firehose approach. A lot of what he did was improv, just throwing tricks out and seeing what stuck. But he tailors it to his audience and situation. He’s performed versions of The Ritual tons of times, and I think he even provided some videos to magicians about how it’s done well before he went on Fool Us. But The Ritual as performed for those spectators at that show was unique. DaOrtiz is a gobsmackingly talented magician on a technical level, but even more so he is a master of his audience’s wonder and surprise. He sees how they are responding and tailors his act to it.

(For some insight into all of this without giving away what DaOrtiz is doing, watch magician Chris Ramsay’s reaction video. It’s really insightful about what is going on, why it works, and why it is truly special.)

I’ve watched that Fool Us video a bunch and know some of what DaOrtiz is up to and nonetheless I would still have trouble summarizing his routine even now. What dominates my memory is the rapid patter, the endless chaos, and the miracle of finding a card in the chaos. The chaos, in fact, increases the pleasure, because the journey of the whole routine is from chaos to order. It’s not even especially innovative order — as he says, he’s just doing the classic ACAAN (any card at any number), an effect magicians have been creating techniques for since at least the 1940s. (Some of those techniques are ingenious but rely on tricks of mathematics that make the performance less than thrilling, I find. If you have to cut the deck and deal cards again and again, it begins to feel less like magic and more like mechanics, which is what it is. But a satisfying performance doesn’t feel mechanical. DaOrtiz knows this, and that’s why his techniques, chaotic as they may seem, are superior to a lot of the traditional ones.)

Absent simplicity, what Dani DaOrtiz gives us is the relief of order from chaos. This is valuable for teachers, too, because that’s also part of our job. Not simplification — if anything, we should be showing students that the universe is wider and more complex than any of us usually think. (Cosmologists know this well.) But complexity can bring pleasure and also insight. The chosen card does, somehow, appear at the end.

Do we have any order from the chaos here? Can I leave you with anything except a scattered pack of cards?

How’s this: Teachers don’t need to throw out their bag of tricks. But they need to think like a magician and ask themselves, always, what the tricks for. We should not be opening our bag to be tricksy, but rather to evoke surprise, to introduce novelty, to encourage curiosity. When the best magicians fool us, their deception comes from an honest place, a place of mutual participation in illusion and wonder. We probably don’t want to be presenting too many illusions to our students, but we do want to provoke wonder, and we do want to make the classroom a place of mutual participation.

Like Dani DaOrtiz, we can say to our students, “Welcome to my world!” And we can mean it. Welcome. Welcome to magic, to wonder, to learning.