Things which now get buzzed as “AI” (“artificial intelligence”) — large language models, statistical prediction software, image generators, etc. — have infiltrated and infested various industries, tools, and discourses with remarkable speed and gobsmacking hype. AI (I’m not going to keep up the scare quotes, but hope you know that, as Kate Crawford says, AI is neither artificial nor intelligent) has become unavoidable in digital tools, with many of our basic everyday applications now incorporating it in some way or another. The hype from the techmeisters is fierce, reminiscent of other tech bubbles past. There’s even apocalypticism, with claims that the machines will accelerate human extinction.

There’s no need to indulge in sci-fi fantasies of killer computers. We’re doing fine at accelerating extinction without AI, and AI’s mundane, actual harms are real and present dangers.

There are also good uses for some of the new tools that get called AI, and hope for more powerful uses in the future. It’s fun to ask ChatGPT to do stuff and it’s fun to see what uncanny assemblages image generators create. I’ve heard that AI tools are quite good at cleaning up audio files for podcasters. There may still be plenty of places in medicine and science where AI tools can achieve more than could be achieved before.

Nonetheless, I believe it is basically inarguable that there is no ethical use of AI. There are some large, obvious, frequently-debated reasons, ones that any discussion of AI ought to lead with:

1.) This is a technology that requires tremendous resources of energy, water, infrastructure, and thus has a significant impact on the environment;

2.) AI language models are trained on huge amounts of writing that the corporations who own the tools did not get consent to use;

3.) AI image generators are based on huge amounts of art that that the corporations who own the tools did not get consent to use;

4.) AI tools are already putting artists, writers, and other workers out of work;

5.) AI tools have accelerated the demise of any ability to tell whether texts, images, sounds, and videos are human-created, thus increasing the flood of misinformation into our world by orders of magnitude.

6.) AI hype is predictably accelerating the effects of hypercapitalism, with AI now commonly proposed as a way to avoid better funding for, for instance, education and healthcare (instead of better schools and hospitals, poor people get AI teachers and nurses, while rich people get private schools and expensive doctors).

I came up with that list quickly; I’m sure there are other problems with AI, but my point here is not to list all the objections. Nor is it to say those are all incontrovertible, or, for that matter, unsolveable. We could deal with jobs made irrelevant by AI with initiatives for guaranteed income, health care, and housing, for instance, so nobody has to rely on employment to survive.

Any of the five problems I list are arguable, but here’s the point: If you think even one of those items is an ethical problem, then the conclusion must be that there is no ethical use of AI.

This is not to argue that you should not use AI tools, that people who use AI are bad, etc. Rather, it’s about the choices we make. Not using AI seems to me an easy choice. It is not a sacrifice.

We all do countless unethical things every single day, but most of the time we would have to sacrifice at least a bit of comfort and happiness to be more ethical. We can be truly concerned that materials in our cell phones and computers are both harmful for the environment and mined and assembled by people in exploitative and likely even dangerous conditions, including children in mines — and we can still choose, as I do, to prioritize having computers and cell phones over those workers’ comfort, health, and ability to live. People like myself are, in Bruce Robbins’s formulation, beneficiaries of the world’s systems — systems which create much destruction, and to which many other people’s lives are sacrificed.

I also admit there is little to no ethical use of social media, and yet I do use it. I cannot ethically justify my continued use of products owned by obscenely wealthy people, products and people that are destroying democracy, society, and the planet’s biosphere. I get some enjoyment from these tools from seeing what friends and family are up to, and find the tools useful when I need to promote events, writing, etc. But I would be a fool to argue that my use of social media is in any way ethically justified.

I say all this not for purposes of self-flagellation, but to admit the bind for any of us who are not saints and who do hold onto our (ethically dubious) lifestyles. However, I do not think we deserve a get-out-of-jail-free card. We don’t get to say, “I am a white, middle-class American and intend to continue to live that lifestyle, and since my life is already a blight upon the planet, I get to do whatever I want!”

No, we all make choices and try to live with those choices. Sometimes, the maintenance of the general social order becomes the basic ethical organizing principal of our lives: my taxes may contribute to weapons manufacturers and armies that kill people every day, but I don’t think that gives me the right to go shoot my neighbor if I find them annoying. (I’ve written elsewhere about the ways in which being part of the liberal order means outsourcing the violence that sustains your life.) Beyond a general commitment to the social order, one way we live with ourselves when trapped in the bind of an inherently unethical life is by also making ethical choices when and how we can, trying to balance things out to the best of our ability with the least amount of sacrifice. Doing a little tiny bit less harm is still doing less harm — even if we could, if we wanted to, do a lot less harm.

Avoiding (to the best of your ability) the tools that get called AI is really not much of a sacrifice for most people. Thus, it seems to me an easy ethical win. When possible, just don’t use it. It won’t always be possible. It’s baked into too much. But you don’t need to provide aid and encouragement to it. You don’t need to pretend it’s a complex ethical quandary that deserves close academic study. It doesn’t. Your use of AI harms the world. You can choose to avoid that harm and give up very, very little.

Is there a way to move beyond the passive, vaguely ethical choice to avoid AI as best you can and into an active, more ethical resistance? I don’t know. I continue to think about this — writing this post is my first step. I want to encourage more people to make the choice not to use AI. But then what?

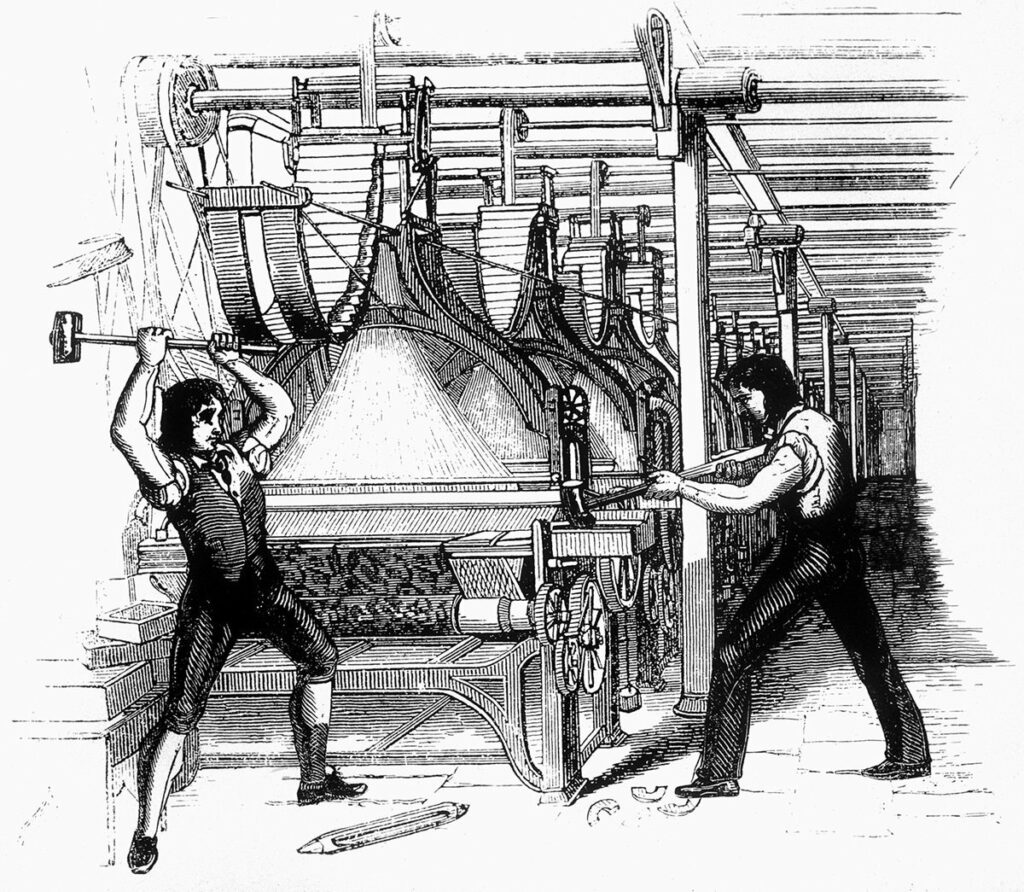

I would be happy to take on the label of Luddite, though I have not earned it, since I have not (yet) smashed any machines. It’s a rather Romantic concept, a bit too filled with the idealism of individual action than a real analysis of systems of oppression; and, in any case, the Luddites lost. Still, the vision of a world that understands technology as both inescapably political and inescapably related to questions of labor and exploitation is an important vision to present. I take seriously James Muldoon’s statement in a discussion of neo-Luddism that

Some workers have increased their autonomy due to new technology such as workers now able to work from home or perform routine tasks with greater ease. Additionally, many new technologies actually do make our lives more convenient, but are often combined with mechanisms that surveil and extract value from us. Understanding how to unravel these complications requires more than a simple opposition to new technology.

There is in fact a possibility for AI to reduce burdensome (often bureaucratic) work, especially if it can become more reliable in its outputs. But this sidesteps some questions: Is AI a tool for making bullshit jobs seem less bullshitty? Is a bullshit job still bullshit if a computer tool does most of it? Maybe it is, and maybe that’s actually a good thing, because perhaps if we have no chance of ending bullshit jobs, at least we can offload them to the algorithms.

My favorite example of this is the loop created by students using ChatGPT and teachers also using AI to grade student work. This frees students and teachers both to do more interesting and productive things, including perhaps new conversations about all the bullshit work of teaching and learning. If assignments in school can so easily be handled by algorithms and statistical language prediction, then perhaps those assignments are, in fact, a waste of everybody’s time, and we should just give them to the machines.

The question of resistance to AI is really a question of how to resist the current order of society, an order we can call late capitalism or neoliberalism or technocratic financialism or the triumph of the billionaire techbros. My decision to answer the question of whether to use AI with the Bartlebyian response “I would prefer not to” is not a decision that will have any noticeable effect on the world or provide any real resistance to the forces immiserating many millions of people and destroying the biosphere itself.

I don’t have an answer for how to resist the forces of hypercapitalism and ecocide in any effective way. This morning, writing this, I am thinking of the preface to the English-language edition of Kōhei Saitō’s book Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto, which I’ve just begun reading. In that preface, Saitō tells the story of a Japanese man who approached him after a lecture, saying he had been convinced by Saitō’s ideas, that he wanted to do something to make the rubber trading company he owned less destructive to the planet and society, but he didn’t know what to do. Saitō writes:

…actually, the answer to his question was in my book as well as in my lecture. Perhaps he had overlooked it or wanted another one that involved less change. My answer was that he should sign his business over to its employees. Since capitalism is the ultimate cause of climate breakdown, it is necessary to transition to a steady-state economy. All companies therefore need to become cooperatives or cease trading.

“Easier said than done!” is the inevitable response, but the response to that response must be: Why? What prevents you, the owner of a business, from making it a workers’ cooperative? (I will leave aside the question of whether that would help stave off the destruction of the biosphere, a question on which I am ignorant. I do think workers’ cooperatives are better than traditional capitalism, but that’s because I believe in the idea of from each according to their ability to each according to their need, which is another way to say: the golden rule.) If you really want to make a change for the good, why don’t you? The billionaires who rule the world do not make this choice — Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk could end world hunger, but instead they choose to buy yachts and space rockets — but this does not mean you have to be as terrible a person as them. You can change your life, you can change your business. You just have to actually want to, or else stop lying to yourself.

But no, I do not know how to resist the all-consuming monster that is the way of life for people like myself and people who are richer and more powerful than myself. I do not know how to convince billionaires to stop funding vanity projects and instead contribute to the good of the world that let them become absurdly rich. I do not know how to change the structures that empower billionaires, the structures that make billionaires possible. I do not know how to overcome the fact that all the systems and instincts of society prevent us from using the knowledge and resources we have to make life quite pleasant for most if not all of the people currently alive.

What I know is that AI’s use of resources is fundamentally destructive, and that abstaining from using such tools isn’t really much of a sacrifice. Therefore, whenever given a choice, I will choose not to use the tools that get called AI.

I’m trying to keep this statement succinct, but here is some further reading if you find what I have said here too blunt or simplified:

- “Generative AI’s environmental costs are soaring — and mostly secret” by Kate Crawford

- “The Map Is Eating the Territory: The Political Economy of AI” by Henry Farrell

- “AI’s excessive water consumption threatens to drown out its environmental contributions” by Joyeeta Gupta, Hilmer Bosch, and Luc van Vliet

- “Here Lies the Internet, Murdered by Generative AI” by Erik Hoel

- “Water worries flood in as chip industry and AI models grow thirstier” by Dan Robinson

- Coverage of AI controversies among writers, artists, and publishers by Jason Sanford

- “The Insecurity Machine” by Astra Taylor (not about AI specifically, but helpful to any discussion of it)

- “AI in Education Is a Public Problem” by Ben Williamson

- “AI is producing ‘fake’ Indigenous art trained on real artists’ work without permission” by Cam Wilson

- “AI is turbocharging disinformation attacks on voters, especially in communities of color” by Bill Wong and Mindy Romero

- “Subprime Intelligence” by Edward Zitron

(image above of Luddites smashing looms via Jacobin)

Plus a million to all of this, though I do keep coming back to the question of what our role is as college teachers with AI at this precise moment in history. Do we teach the threats and dangers and the affordances (that for us are part of the threats and dangers) and encourage students to create their own opinions and paths? Or is that a way of enabling rather than resisting something truly counter to the values inherent in our public mission? Or, in another light, is that impossible to do without some “use?” I think about art and writing classes, and the difference between “teaching” AI as a tool and “teaching” it as a political and economic and social influence, and how you discuss the latter without investigating the former. Anyway, I love this piece for faculty– something to start with instead of “10 timesaving uses of ChatGPT for Writing Papers” or whatever…

Thanks! Yes, I think there are extra challenges in teaching, but I tend to think of it as teaching about, say, poisons. It’s possible to do so without drinking them. The analogy falls apart in some ways, but as with so much, it goes back to intentionality. It’s the only way to live through the many binds we live in. Be as informed as we can be, as honest as we can be. In teaching, we know there are often no great answers. So we can’t be looking for the perfect way to do something, the way free of all error. Instead, the least terrible practical question is: How do I want to be wrong?